Starlink’s huge ambition and deployment plan may clash with reality

Starlink’s first mission of 2022 launched another 49 satellites into orbit, extending its grand total to nearly 2,000. But since completing its first orbital shell of about 1,600 satellites last May, “Starlink’s launch frequency has slowed dramatically with only four rocket launches over the past seven months, or roughly one every seven weeks,” explained Craig Moffett, principal analyst at MoffettNathanson in a note to clients. Craig wrote:

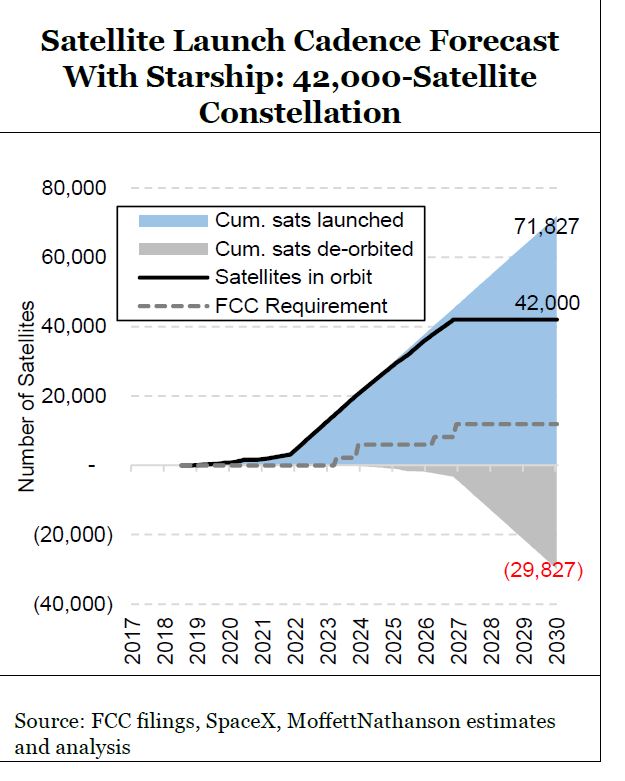

Starlink’s ambition is huge (a constellation of as many as 42,000 satellites). And the implied valuation for the still-private company is huge ($100B+ for all of SpaceX).

This “hugeness” has captured investors’ imaginations and no doubt hugeness itself is very much part of its appeal. But we haven’t yet seen investors come to grips with all of the implications of this bigness. We were struck by Elon Musk’s recent tweet conceding a “genuine risk of bankruptcy” – immediately dismissed by some as hyperbole – and it got us thinking about scale, and risk, in ways we really hadn’t considered before.

Moffett notes that the new Starlink V1.5 satellites are heavier, leading to fewer satellites per launch. “At a payload of 50 satellites per launch for Falcon 9 rockets – down from 60 per launch for V1.0 satellites – SpaceX would need to drastically increase launch frequency to once every seven days for five consecutive years just to launch the satellites required for their planned constellation of ~12,000 by their FCC deadline in 2027.”

In low-Earth orbit, satellites will drift back to Earth and burn up on re-entry. Assuming the satellites have an average lifespan of five years, the number of launches to simply replace expiring satellites will, by year five, be as large as the number of launches required over the next five years to grow the constellation. By the end of 2030, just nine years from now, they would have had to launch nearly 23,000 satellites in support of a 12,000 bird constellation. Assuming a Falcon 9 payload of 50 satellites, that would imply 48 launches each year – roughly one every seven days – just to sustain a constellation of 12,000 satellites even after the constellation is “finished.”

Privately held SpaceX (Starlink’s owner) will also need to strongly increase manufacturing capacity and manage tricky supply chain logistics to meet the needs for Starlink, as well as for SpaceX’s clients.

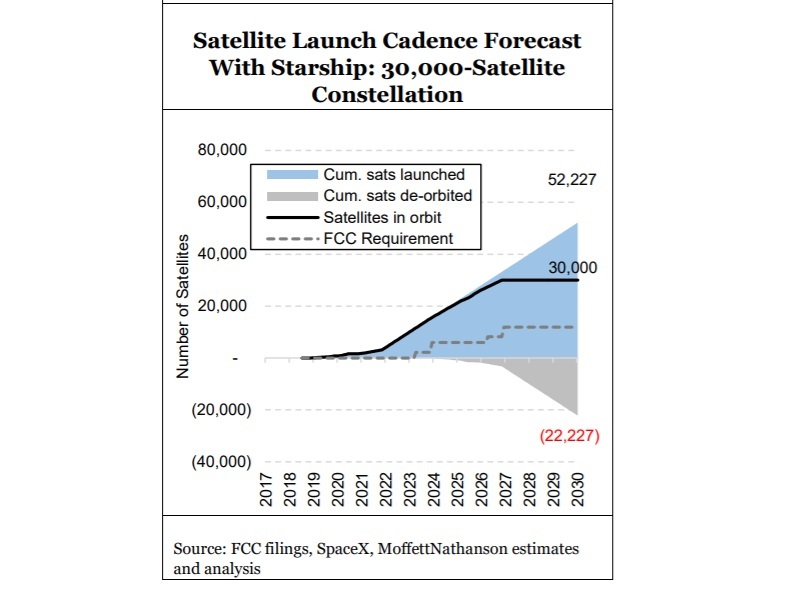

Based on $30 million per launch, Moffett estimates that it would cost about $15 billion to build a constellation of 30,000 satellites, with satellite replacement (production and launch) alone costing more than $3.6 billion per year. Please see chart below.

Starlink hopes to beef up its capabilities with Starship, a larger launch vehicle that’s had its share of problems, with an orbital test flight that could take place as soon as March. However, Craig suggests that Starship isn’t necessarily the answer to the problem, considering that new V2.0 satellites will be perhaps four times as massive as previous generation Starlink LEO satellites.

In November 2021, Elon Musk distributed a companywide email stating that a production crisis centered on the Starship rocket engine puts SpaceX on a path to “genuine risk of bankruptcy if we cannot achieve a Starship flight rate of at least once every two weeks next year.”

However, the costs will be very high. Moffett says the “sustenance” cost of the constellation, before considering any costs associated with overhead, engineering, ground facilities, network operations centers, or end-user support, installation, and/or maintenance, could tally $5B per year as per this chart:

Satellite projects are, by their very nature, huge. A defining characteristic of big infrastructure investments is that they demand that investors be confident about the success and payoffs from infrastructures that may take as much as a decade to build.

Moffett is concerned that investors [1.] have yet to “come to grips with all of the implications” of the audaciousness of the Starlink’s huge ambitions.

Note 1. It’s important to note that Starlink is part of SpaceX, which is still a privately owned company. As of October 2021, Barron’s said that “Elon Musk owns roughly 50% of SpaceX.” It is not known who or whom owns the other half of SpaceX

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

References:

https://www.barrons.com/articles/elon-musk-net-worth-trillionaire-51634679420?tesla=y

3 thoughts on “Starlink’s huge ambition and deployment plan may clash with reality”

Comments are closed.

Good article, Alan as it is the first I have seen that really does such a thorough job examing the operational costs of launching and maintaining the huge fleet of satellites. It will be interesting to see whether or not Starlink/SpaceX can drive down the launch costs and costs of the satellites fast enough that they don’t burn through their cash, like their satellites will burn upon re-entry to the atmosphere.

One also has to wonder about the environmental impact of satellites that literally burn up, as well as the impact of that many rocket launches. Of course, there are already concerns from astronomers about light pollution.

SpaceX has launched hundreds of internet-beaming satellites to orbit in recent years, stoking fears from some scientists that the small, relatively low-orbiting satellites could make astronomy harder.

The new study, in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, found that 5,301 streaks from Starlink satellites popped up in photos taken by the Zwicky Transient Facility near San Diego from November 2019 to September 2021.

That’s an increase from 0.5% of twilight images being affected in 2019 to nearly 20%.

The team behind the study found the Starlink streaks mostly appeared in twilight images, which are key to finding potentially dangerous asteroids and comets that come from the same part of the sky as the Sun.

“We don’t expect Starlink satellites to affect non-twilight images, but if the satellite constellation of other companies goes into higher orbits, this could cause problems for non-twilight observations,” Przemek Mróz, one of the authors of the new study, said in a statement.

If SpaceX does eventually manage to create a constellation of about 10,000 satellites, the authors of the study expect every twilight image taken by the ZTF to have a streak from a Starlink satellite in it.

But, but, but: Those satellite streaks may not actually matter all that much for scientific observations with the telescope.

“There is a small chance that we would miss an asteroid or another event hidden behind a satellite streak, but compared to the impact of weather, such as a cloudy sky, these are rather small effects for ZTF,” Tom Prince, another author of the study, said.

However, other observatories, like the Vera Rubin Observatory — expected to start science operations next year — could have more outsized effects from Starlink due to its sensitive optics.

https://www.yahoo.com/entertainment/study-spacex-starlink-satellites-seen-182911935.html

Bloomberg: Musk’s Starlink Brings Internet to Ukraine, and Attention to a New Space Race

SpaceX enabled its Starlink satellite broadband service in Ukraine and began shipping additional dishes. Those dishes are especially valuable now that Russia’s military is targeting Ukrainian infrastructure. “Received the second shipment of Starlink stations!” Mykhailo Fedorov, Ukraine’s minister of digital transformation, tweeted on March 9. “@elonmusk keeps his word!”

The dishes Starlink’s Elon Musk has provided to Ukraine and to Tonga following its January tsunami have cast a spotlight on low-Earth-orbit (LEO) satellites, a new generation of spacecraft that can circle the globe in just 90 minutes and connect users to the internet. They’re small and inexpensive: A Starlink satellite weighs 260 kilograms (573 pounds) and costs from $250,000 to $500,000, while an Inmarsat Group Holdings Ltd. geostationary satellite can clock in at 4 metric tons and sell for $130 million.

The satellite networks will be able to provide broadband access to tens of millions of people in places such as rural India that otherwise lack access to more traditional mobile and fixed-line networks. “There is a large opportunity to bridge the digital divide in remote areas where the cost of terrestrial communication is high, and hence both voice and broadband communication have not been set up,” says Anil Bhatt, director general of the Indian Space Association.

On March 9, Musk boasted that SpaceX had sent 48 more satellites into orbit, adding to its over 2,000 already circling the Earth. But Musk has rivals with their own LEO satellite ambitions. They include fellow space billionaire Jeff Bezos. Amazon.com Inc.’s Kuiper Systems wants to launch more than 7,000 satellites. On March 5 a Chinese rocket launched six LEO satellites for Beijing-based GalaxySpace, which plans a constellation with as many as 1,000. The European Union in February announced a plan for a constellation that would cost about €6 billion ($6.6 billion). And Indian billionaire Sunil Mittal’s Bharti Global, along with the British government, is an investor in OneWeb Ltd., which plans to begin operating its LEO constellation of 648 satellites this year. It intended to launch its latest group of satellites on March 5 aboard a Russian rocket, but canceled after the Kremlin’s space agency demanded that the U.K. sell its stake. OneWeb is looking for alternative services for six future launches.

Unlike more established operators, which have a relatively small number of satellites in fixed locations about 36,000 kilometers (22,369 miles) above sea level, companies launching LEO satellites place them at heights of 550 to 1,200 km. That makes it easier for the satellites to provide speedy services than those higher in space, says Marco Caceres, an analyst with Teal Group, an aerospace and defense market analysis firm. “They’re going to make a lot of these traditional systems dinosaurs overnight,” he says, adding that Starlink alone is likely to have 4,500 satellites in operation by the middle of the decade. “They’re moving at lightning speed.”

SpaceX began signing up customers in India in 2021 even though it didn’t have a license to offer Starlink service there. India’s government in January demanded the company return money from would-be customers. As SpaceX works out its entry strategy for India, Reliance Jio Infocomm Ltd.—the telecommunications operator controlled by Mukesh Ambani, India’s richest person—in February formed a joint venture with Luxembourg-based satellite operator SES SA to provide internet access via satellites in geostationary and medium-Earth orbits.

While the new satellite companies boast of their ability to reach underserved communities, many will struggle to make their equipment affordable for some target markets, says Bloomberg Intelligence analyst Matthew Bloxham. According to BI, a standard Starlink plan costs $499 for the hardware, plus a monthly fee of $99. But there are other reasons governments are likely to provide financial support for internet via satellite, Bloxham says: “It provides resilience in case of a cyberattack that takes out the regular internet that we know today.”

Still, critics say Musk and others aren’t considering the risks of having too many satellites in a relatively narrow band above Earth. “What’s going on now is there’s a race to put up as many as possible for the rights that are implied by having those satellites, even if it’s not economically justified, or safe, or sustainable,” says Mark Dankberg, chairman of Viasat Inc., a California-based satellite operator of geostationary satellites, which in November agreed to buy rival Inmarsat for $4 billion. As operators attempted to bulk up in response to the challenge from newcomers, M&A deal volume for the satellite industry in 2021 reached its highest level since 2007, according to data compiled by Bloomberg, with companies signing 60 deals worth $18 billion.

China in December said two of Starlink’s satellites came dangerously close to its space station. The U.S. said there had been no “significant probability” of a Starlink collision with the Chinese station, but some experts worry that the situation was a sign of what’s to come. International agreements governing space date to the 1960s and ’70s, when billionaires didn’t have their own space programs. “We have so many of these new actors coming on board, and we don’t have sufficiently strong international law,” says Maria Pozza, a director at Gravity Lawyers in Christchurch, New Zealand, who advises clients on space law and regulation. “We’ve got a little bit of a mess.”

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-03-16/musk-bezos-satellite-companies-target-low-orbit-networks