Cuba

Empresa de Telecomunicaciones de Cuba in its worst ever state; saddled with worthless Cuban pesos

Cuba’s national monopoly telco, Etecsa (Empresa de Telecomunicaciones de Cuba) is chronically starved of the foreign currency which it needs to buy telecom infrastructure equipment, such as cables and network hardware. Etecsa only has Cuban pesos, which are completely worthless outside its borders. No company in any other country will accept pesos in payment for anything.

Translating Cuba, which has translated and published a 14ymedio article in English, we have learned that the state-owned telco has been fined by the government for failing to spend its entire 2024 peso budget, even though it tried to do so. The island’s network operator had already told the authorities that it had underspent by many millions of pesos because no foreign company will accept them in payment either for goods or services.

The proposed solution was to designate the underspent cash as profit and then divide it up between Etecsa employees, but the Cuban government objected, fined the telco, and sequestered the cash.

To prevent the scenario from being repeated this year, Etecsa is preparing new payment methods for its services to collect as much hard currency as it can.

“Several scenarios have been evaluated, and so far the one that seems the best is to limit the number of recharges in national currency for the same customer. When he gets down to a certain monthly amount, he will have to recharge in dollars,” clarifies the administrator. “Together with the recharges from abroad, the purchase in Cuba will be enabled, directly in dollars or with a Classic card.”

“What happens now is that mobile phone customers sometimes have thousands of pesos left and can buy as many navigation packages as they want. They can even make transfers of that money so that others can buy a connection package. It will remain limited, because there’s not much Etecsa can do with that Cuban money. It’s worthless for investments and purchasing infrastructure.”

“We are just now restructuring everything, and that is one of the reasons why we are removing some monthly offers of recharges with a bonus, because there are many customers whose relatives abroad buy the recharge for them, which includes a balance and a recharge package, but then they resell it to others who pay them in Cuban pesos, and these in turn buy new navigation packages. We even know that many relatives send them dollars, and they change them on the black market and buy the packages in national currency. So Etecsa doesn’t earn foreign exchange and can’t go on like this because this is a telecommunications company and has to earn a lot of money.”

“We are tying pieces of cables together to repair the breaks,” one Etecsa employee told 14ymedio, adding that the company is going through “the worst crisis since its creation.” As a result of the foreign currency crisis, in 2022 the telco was unable to “fulfill its financial commitment to Nokia,” the island’s mobile data infrastructure supplier.

For the 2025 budget, the Minister of Finance and Prices, Vladimir Regueiro Ale, has warned that a “special tax on telecommunications services” will be implemented. According to the owner, “this will generate a tax in addition to the invoices from the Cuban Telecommunications Company of more than 13 billion pesos,” a sea of national currency for some dollar-thirsty coffers. That sounds like a lot, but it’s currently the equivalent of $542m and it’s useless Cuban pesos…That won’t help Etecsa which is in its worst ever state, unable to make basic repairs or replace the batteries that power mobile network sites.

“There are no land lines to replace, we lack the boxes for home installation, and there are also many problems with supplying cables.”

The lack of liquidity has been taking its toll on Etecsa for years, especially with its foreign investors. In 2022, for the first time in 15 years, the company could not fulfill its financial commitment to Nokia, the Finnish company that has worked on the Island implementing the data service for mobile telephony.

References:

Etecsa Will Start Charging for Some Services in Dollars Inside Cuba

Telecom data traffic in Cuba grows 10% due to COVID-19; Free access to EnZona e-commerce platform

What’s the real status of Internet access in Cuba?

Cuba-Google agreement to speed up Internet access on the island

Reason magazine: How Internet Access Is Changing Cuba; Project Loon revisited?

IN JULY, thousands of Cubans in dozens of cities took to the streets to protest the island nation’s Communist dictatorship and chronic shortages in food, energy, and medicine, all of which have been made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic. These were the biggest anti-government demonstrations in Cuba in decades. They were enabled by social media and the internet, which came to Cuba in a big way only in late 2018, when President Miguel Diaz-Canel allowed citizens access to data plans on their cellphones.

To better understand exactly how Facebook, YouTube, WhatsApp, and other online platforms are connecting the Cuban people and under-mining state control, Reason’s Nick Gillespie spoke with Ted Henken, who teaches sociology and Latin American studies at City University of New York’s Baruch College and is the co-editor of Cuba’s Digital Revolution (University Press of Florida).

Q: How did the internet come to Cuba?

A: You basically had a period in the ’90s when Cuba was actually pretty advanced in the region in terms of its networking and internet, but Fidel [Castro] called it “a wild colt that needed to be tamed.” They saw it as a mortal threat because it undermined monopoly information control, which is one of the fundamental hallmarks of the Cuban system.

When Raul Castro became president in 2008 and gradually thereafter, Cubans started getting very gradually online. They started getting cellphones. They started to be able to buy and use laptop computers. Internet grew from 3 percent connectivity in about 2008 to 15 or 20 percent by around 2015, enabled partly by the government rollout of internet cafes. The next big thing was that Cubans got Wi-Fi hot spots, set up largely in public parks.

Q: Why did Cuba eventually allow people to use mobile internet on their phones?

A: Because of accumulated pressure and demand. But the other reason is that Cuba is in constant economic crisis. It’s inefficient. It’s unproductive. The system is totally lacking in incentive structures. So the government sees internet access as a cash cow, because it is the sole internet provider through its telecom monopoly.

Q: The demonstrations you documented online weren’t just happening in Havana, right?

A: Exactly. This is what’s unprecedented about them. Even if one of these had happened, it would be quite surprising in Cuba. But the fact that they happened simultaneously and probably between 30 and 50 places around the country is amazing.

Q: What are the ways in which people are using the internet to either protest or share images of protests?

A: You can kind of break the apps that Cubans use in terms of what we’re talking about into two groups: ones that allow horizontal, encrypted, private communication, and others that are broadcast media. Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter are the go-to apps to share with the world what’s going on, including live broadcast in Cuba. A fourth channel is, of course, YouTube. Interestingly enough, President Diaz-Canel angrily gave YouTube an endorsement when he blamed [the protests] on these irresponsible, mercenary YouTubers and influencers.

Q: If you’re doing something on Facebook or YouTube, you are totally public. The government knows exactly who you are.

A: Exactly. That’s been a change over the last, let’s say, 15 years. One of the things they were chanting in the street was, “We’re not afraid.”

A key part of the control in Cuba is keeping people afraid, keeping them isolated from one another and not realizing that other people share their concerns or their complaints, and keeping them afraid of sticking their head up and getting it chopped off. The internet has helped mitigate both of those, because they see other people who share their concerns. And then that helps them lose their fear.

So there’s a lot of people who are out of the political closet, so to speak, in Cuba, who say the same thing in public as they would say in private.

This interview has been condensed and edited for style and clarity. For a podcast version, subscribe to The Reason Interview With Nick Gillespie.

Source: Reason November 2021 issue

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

“Internet access for the Cuban people is of critical importance as they stand up against the repressive Communist government,” Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis, a Republican, wrote in a letter to the White House earlier this month, urging President Joe Biden to provide “all necessary authorizations, indemnifications, and funding to American businesses” to get Cubans back online. He noted that the crackdown on internet access in Cuba has left many Floridians without the ability to communicate with loved ones on the island.

DeSantis has become one of the leading advocates, along with Reps. Maria Salazar (R–Fla.) and Carlos Gimenez (R–Fla.), both of whom are Cuban-American, for a radical plan to beam mobile internet service into Cuba from balloons anchored offshore that would effectively serve as temporary cell towers. It’s an idea that would rely on the technological know-how of Google and the diplomatic might of the United States—and even then it might be of limited value. But it might, as DeSantis put it in his letter to Biden, also be “the key to finally bringing democracy to the island” without the need for military intervention.

The diplomatic and political dynamics are actually more straightforward than they might appear. There are plenty of precedents for beaming signals across international borders against the wishes of a domestic government. Radio Free Europe is probably the most famous example, but the better comparison here is Radio Televisión Martí, run by the U.S. Agency for Global Media, which has broadcast news into Cuba since the 1980s. Clearly, the U.S. has no qualms about whatever international laws it might be violating by sending television signals into Cuba against the Cuban regime’s wishes. Sending mobile internet signals is a difference of degree—a slightly different wavelength of light—but should not require a total overhaul of U.S. policy toward Cuba.

“It is time to build on [the Radio Televisión Martí] model and include the delivery of Internet service,” argues Brandon Carr, one of the five commissioners in charge of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

Still, due to the diplomatic issues involved, any effort to beam internet into Cuba would have to be cleared by the White House. Earlier this month, press secretary Jen Psaki said the Biden administration was “actively pursuing measures” to “make the internet more accessible to the Cuban people.”

It’s not a slam dunk, of course. Signals could be jammed by the Cuban government, which already tries to block Radio Televisión Martí as much as possible. Many Cubans’ cell phones might not be able to connect due to differences in network protocols. And whatever connectivity is possible will be slow and spotty, at least by American standards.

But it may be worth making the attempt anyway, particularly since the technology already exists and could be deployed for minimal cost. There’s little to lose, and much that could be gained—not just in Cuba, but in other fights against tyrannical regimes.

“Internet shutdowns are increasingly becoming a tool of tyranny for authoritarian regimes across the globe,” says Carr. “America must stand against this anti-democratic tactic and move with haste to provide internet freedom to the Cuban people.”

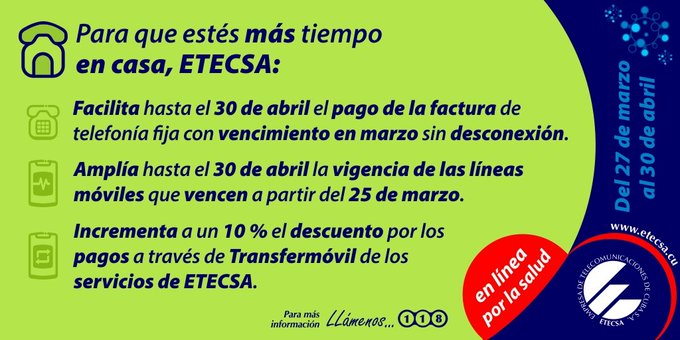

Telecom data traffic in Cuba grows 10% due to COVID-19; Free access to EnZona e-commerce platform

Cuba state owned telecom company ETECSA president Mayra Arevich posted on her Twitter account @MayraArevich on Thursday:

“The traffic growth for (last) three days is more than 10% of additional volume on our networks”

The ETECSA official also urged not to use large volumes of data on the mobile network so that the traffic capacity can be shared among all, after noting that navigation requires seven times more resources than voice calls.

“To think as a country is to maintain the stability of our systems to guarantee services to our population. We advise you not to use large volumes of data on the mobile network, so that the traffic capacity can be shared among all,” said the executive president of the state enterprise, Mayra Arevich, quoted by the official Cubadebate site.

These (voice calls) guarantee the fundamental communications with the emergency services and our health system,’ Arevich wrote in another tweet quoted Friday by Cuba’s Granma newspaper after social media were flooded with requests for the telephone company to lower rates.

ETECSA guarantees voice/data network stability at this time of constant surveillance on the coronavirus pandemic, with which more than 465,000 people have already been infected in 200 countries, she said.

Cuba Communications Minister Jorge Luis Perdomo said this Thursday that the measures to fight coronavirus were conceived with integrity.

On Friday, Mayra Arevich Marín tweeted: “Starting today, March 27, 2020, you can access the #EnZona platform, an e-commerce application, which together with #Transfermóvil are the forefront of computerization in our society, free of charge.”

Cuba-Google agreement to speed up Internet access on the island

Google and ETECSA signed a memorandum of understanding to begin the negotiation of a so-called “peering agreement” that would create a cost-free and direct connection between their two networks. That would enable faster access to content hosted on the Google’s servers, which are not located on the island. Internet in Cuba has been notoriously sluggish and unreliable. In a country where information is tightly controlled, it remains to be seen how much Google’d information would be available in Cuba. That’s if and when a fast connection can be made between Cuba’s ETECSA controlled Internet and Google’s servers.

The agreement creates a joint working group of engineers to figure out how to implement this peering arrangement, likely via an undersea cable. What’s needed first is the creation of a physical connection between Cuba’s network and a Google “point of presence,” the closest ones being in South Florida, Mexico and Colombia. Cuba currently has a single fiber-optic connection running under the Caribbean to Venezuela that has been unable to provide the island with sufficient capacity to support its relatively small but growing group of internet users, for reasons never disclosed by either country’s Communist government. Neither Cuban or Google officials provided any estimated timeframe for the island’s connection to a new undersea fiber-optic cable. That step could take years given the slow pace of Cuba’s bureaucracy and the obstacles thrown up by the U.S. trade embargo on the island.

“The implementation of this internet traffic exchange service is part of the strategy of ETECSA for the development and computerization of the country,” Google and ETECSA said in a joint news release, read out at a news conference in Havana.

“We are excited to have reached this memorandum for the benefit of internet users here in Cuba,” Brett Perlmutter, the head of Google Cuba, said before signing the deal.

References:

https://www.businessinsider.com/google-partners-etecsa-cuba-2019-3

https://phys.org/news/2019-03-cuba-google-island.html

Wi-Fi hotspots in Cuba Create Strong Demand for Internet Access

by Alexandre Meneghini, Sarah Marsh of Reuters

The introduction of Wi-Fi hotspots in Cuban public spaces two years ago has transformed the Communist-run island that had been mostly offline. Nearly half the population of 11 million connected at least once last year.

That has whet Cubans’ appetite for better and cheaper access to the internet.

“A lot has changed,” said Maribel Sosa, 54, after standing for an hour with her daughter at the corner of a park in Havana, video chatting with her family in the United States, laughing and gesticulating at her phone’s screen.

She recalled how she used to queue all night to use a public telephone to speak with her brother for a few minutes after he emigrated to Florida in the 1980s.

Given the relative expense of connecting to the internet, Cubans use it mostly to stay in touch with relatives and friends. Although prices have dropped, the $1.50 hourly tariff represents 5 percent of the average monthly state salary of $30.

“A lot more could change still,” said Sosa. “Why shouldn’t we be able to have internet at home?”

A tiny share of homes has had broadband access until now, subject to government permission granted to some professionals such as academics and journalists.

The state telecoms monopoly has vowed to hook up the whole island and connected several hundred Havana homes late last year as a pilot project. In September, it said it would roll that service out nationwide by the end of 2017.

Cubans say previous promises for such access have not been fulfilled, so their expectations are not high. They also say the cost is prohibitive, with the cheapest monthly subscription priced at $15.

Cubans use their mobile devices to connect to the Internet via WiFi Hotspot near their street.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Havana says it has been slow to develop network infrastructure because of high costs, attributed partly to the U.S. trade embargo. Critics say the government fears losing control.

Cubans who can afford it flock to Internet cafes and 432 outdoor hotspots where they brave ants, mosquitoes and the elements.

Here they laugh, cry, shout, and whisper. Black market vendors weave in and out among them, trying to hawk pre-paid scratchcards allowing Wi-Fi access. The ping of incoming messages and ring of calls fill the air.

“There’s absolutely no privacy here,” said Daniel Hernandez, 26, a tourist guide, after video chatting with his girlfriend in Britain.

“When I have sensitive things to talk about, I try shutting myself into my car and talking quietly.”

The quality of connections is often good only at specific spots, he said, and when fewer users are connected. Otherwise, the screen tends to freeze mid-chat.

Hernandez said he also uses the internet to search for news. In Cuba, the state has the monopoly on print and broadcast media.

A few meters further on, Rene Almeida, 62, sat in his taxi checking email. He said he felt lucky that his two children had moved to the United States where communications are better than ever. It was only in 2008 that the government first allowed Cubans to own cell phones.

He, too, complained of the lack of privacy and the expense.

“It’s better than nothing,” he said. “But it should improve. It will.”

…………………………………………………………………………………………………

References:

https://techblog.comsoc.org/2017/08/18/whats-the-real-status-of-internet-access-in-cuba/

What’s the real status of Internet access in Cuba?

by Matteo Ceurvels of eMarketer (edited with Notes by Alan J Weissberger)

Few people in Cuba have regular access to the Internet, and those who do encounter slow download speeds, according to an eMarketer study. Although Cuba’s state-run service provider (see details below) has built WiFi hotspots throughout the country, the relatively high rate of $1.50 an hour is too much for most Cubans to pay. [Please see references below for additional information on the WiFi hotspots in Cuba- mostly in Havana]

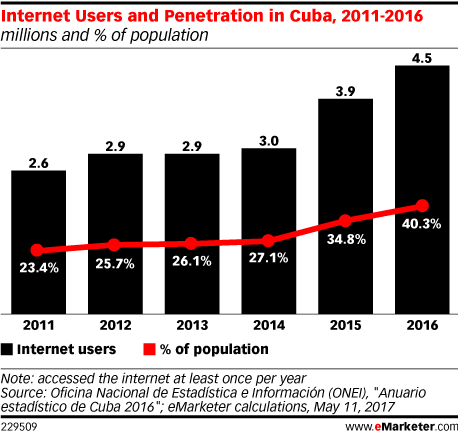

eMarketer estimates that there will be 360.4 million internet users in Latin America in 2017. While the market research firm does not break out specific metrics for Cuba, the latest figures from the government’s National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI) show that over 4.5 million people, or roughly 40.3% of the total population, accessed the Internet at least once during 2016.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Editor’s Note: The actual ONEI ICT report (via Google Translate) states that for 2016 there were 403 people that accessed the Internet out of every 1,000 people living on the island. That compares with 348, 271, 261, 257 and 232 people for the years 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012, 2011, respectively.

The same report (which I don’t trust) says the mobile population coverage (not usage) has been 85.3% of the population from 2012-2016, up from 83.7% in 2011.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………..

The number of people with internet access in their homes was significantly lower: The BBC reported in March of last year that the at-home internet penetration rate was roughly 5%.

Web access in the country remains relegated to a few options. State-run telecom Empresa de Telecomunicaciones de Cuba S.A. (ETECSA), which first began offering public Wi-Fi spots in 2015, claims to provide 391 such spots across the country. But at a cost of about $1.50 per hour, access remains too expensive for most Cubans, and internet speeds are reportedly excruciatingly slow.

ETECSA also began a pilot program in December of last year to provide some 2,000 users in Havana, Cuba’s capital, with fixed broadband internet access for a free two-month trial period. In March, ETECSA said 358 participants in the program signed up to pay for the service, which offered data speeds of between 128 kilobits per second (Kbps) and 2 megabits per second (Mbps).

And when residents of the country do manage to get online, they are subject to strict internet censorship overseen by the government. Some websites and services are blocked, and communications can easily be monitored by government figures.

During parliamentary sessions held in July, Vice President Miguel Díaz-Canel acknowledged that Cuba has one of the lowest internet access rates, but rejected the notion that its society was “fully disconnected.”

He added that tech companies that had entered into agreements with the country’s government to provide them with the infrastructure necessary to expand internet access had been met with “fierce financial prosecution.”

Despite these claims, the government has sought out partnerships with some of the world’s leading tech companies. In April, Google brought servers in the country online for the first time, making it the first foreign tech firm to host its own content in Cuba.

At the parliamentary sessions, Díaz-Canel also claimed that the penetration of social media platforms had grown by 346% in 2016. (The government did not respond to eMarketer’s request to verify this figure.)

However, Martín Utreras, vice president of forecasting at eMarketer, noted that the majority of social media users in the country were most likely foreign tourists looking to stay connected while on vacation.

According to data from StatCounter, there are signs that Facebook is a leading social media platform in the country. Facebook was responsible for 83.3% of page views resulting from social network referrals in Cuba in July, more than either Pinterest (8.4%) or Twitter (4.3%). (StatCounter’s figures take into consideration website referral traffic from both locals and visitors in Cuba.)

Despite signs that internet access is increasing in the country, Cuba still has a long way to go before getting online is something residents consider normal. In fact, many in the country rely on “el paquete semanal,” or the weekly package—a hard drive that is loaded with contraband content such as news, music, TV shows and other videos and passed from person to person.

“Cuba’s journey resembles that of similar trends we’ve seen in the case of China or Vietnam,” Utreras said. “Although Cuba is still many years behind in terms of private telecom investment, infrastructure development and overall internet adoption, by comparison, the immediate future will most likely be driven by government interests rather than the market itself.”

……………………………………………………………………………………………..

References:

https://www.emarketer.com/Article/Cuba-on-Slow-Crawl-Toward-Increased-Internet-Access/1016352

http://www.one.cu/aec2016/17%20Tecnologias%20de%20la%20Informacion.pdf

http://www.businessinsider.com/is-there-internet-in-cuba-2017-1

https://insightcuba.com/blog/2017/03/05/havanas-wifi-hotspots-and-getting-online-cuba

Cuba to expand Internet access and lower price of WiFi connections