Starlink

U.S. BEAD overhaul to benefit Starlink/SpaceX at the expense of fiber broadband providers

The U.S. The Commerce Department is examining changes to the NTIA’s $42.5 billion broadband funding bill (Broadband Equity Access and Deployment- BEAD), which endeavors to expand internet access in underserved/unserved areas. [BEAD was part of the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) during the Biden administration] The proposed new rules will make it much easier for Elon Musk owned Starlink satellite-internet service, to tap in to rural broadband funding, according to the Wall Street Journal. [Starlink is owned by SpaceX which is majority owned by Elon Musk).

Commerce Department Secretary Howard Lutnick said that BEAD will be revamped “to take a tech-neutral approach that is rigorously driven by outcomes, so states can provide internet access for the lowest cost.” The department is also “exploring ways to cut government red tape that slows down infrastructure construction. We will work with states and territories to quickly get rid of the delays and the waste. Thereafter, we will move quickly to implementation in order to get households connected. All Americans will receive the benefit of the bargain that Congress intended for BEAD. We’re going to deliver high-speed internet access, and we will do it efficiently and effectively at the lowest cost to taxpayers.”

By making the broadband the grant program “technology-neutral,” it will free up states to award more funds to satellite-internet providers such as Starlink, rather than mainly to companies that lay fiber-optic cables which connect the millions of U.S. households that lack high-speed internet service.

The potential new rules could greatly increase the share of funding available to Starlink. Under the BEAD program’s original rules, Starlink was expected to get up to $4.1 billion, said people familiar with the matter. With Commerce’s overhaul, Starlink, a unit of Musk’s SpaceX, could receive $10 billion to $20 billion.

“The Trump administration is committed to slashing government bureaucracy and harnessing cutting-edge technology to deliver real results for the American people, especially rural Americans who were left behind” under the Biden administration, White House spokesman Kush Desai said.

“Leave it alone; let the states do what they’ve done,” Missouri State Rep. Louis Riggs, a Republican, said in a recent interview. “The feds could not do what the states have done. In 10 or 15 years, all they basically did, they walked in and screwed everything up. God love them, they just keep throwing money at the problem, which is okay when you give it to the states and let us do our jobs, but trying to claw that funding back and stand up a new grant round is the worst idea I’ve heard in a very long time, and that’s saying a lot coming out of D.C.”

The overhaul could be announced as soon as this week, possibly without some details in place, the people said. Following any changes, states might have to rewrite their plans for how to spend their funding from the program, which could delay the implementation.

Lutnick told Commerce staff he plans to do away with other BEAD program rules, including some related to climate impact and sustainability, as well as provisions that encouraged states to fund companies with a racially diverse workforce or union participation, the people said. The program requires internet-service providers that receive funding to offer affordable plans for lower-income customers. Lutnick saids he is considering reducing those obligations.

Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick at the White House last month. Photo: Francis Chung/Pool/Cnp/ZUMA Press

Many broadband providers worried the Musk-led Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) would eliminate or reduce the program’s funding. Is that not a conflict of interest considering that Musk owns Starlink/SpaceX?

Given the overhaul, fiber broadband providers may not benefit from it as much as they expected because non-fiber technologies are poised to receive more funding than before.

Fiber Broadband Association CEO Gary Bolton said in a statement that all “Americans deserve fiber for their critical broadband infrastructure. Fiber provides significantly better performance on every metric, such as broadband speeds, capacity, lowest latency and jitter, highest resiliency, sustainability and provides the maximum benefit for economic development and is required for AI, Quantum Networking, smart grid modernization, public safety, 5G and the future of mobile wireless communications. We urge our policymakers to do what’s right for people and to not penalize Americans for where they live or their current income levels.”

Telecommunications and broadband consultant John Greene wrote that states that have started the sub-grantee selection process, such as Louisiana, “might be forced to rethink their process in light of potential new rules.” Other “states, like Texas, might be better served to pause their process until after Commerce has completed their review and made any necessary changes,” he said.

References:

Nokia will manufacture broadband network electronics in U.S. for BEAD program

New FCC Chairman Carr Seen Clarifying Space Rules and Streamlining Approvals Process

Highlights of FiberConnect 2024: PON-related products dominate

Telstra selects SpaceX’s Starlink to bring Satellite-to-Mobile text messaging to its customers in Australia

Australia’s Telstra currently works with Space X’s Starlink to provide low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellite home and small business Internet services. Today, the company announced it will be adding direct-to-device (D2D) text messaging services for customers in Australia. We wrote about that in this IEEE Techblog post. Telstra’s new D2D service is currently in the testing phase and not yet available commercially. Telstra forecasts it will be available from most outdoor areas on mainland Australia and Tasmania where there is a direct line of sight to the sky.

Telstra already has the largest and most reliable mobile network in Australia covering 99.7% of the Australian population over an area of 3 million square kilometres, which is more than 1 million square kilometres greater than our nearest competitor. But Australia’s landmass is vast and there will always be large areas where mobile and fixed networks do not reach, and this is where satellite technology will play a complementary role to our existing networks. As satellite technology continues to evolve to support voice, data and IoT Telsa plans to explore opportunities for the commercial launch of those new services.

Telstra previously teamed up with satellite provider Eutelsat OneWeb to deliver OneWeb low-Earth orbit (LEO) mobile backhaul to customers in Australia. The telco said the D2D text messaging service with Starlink will provide improved coverage to customers in regional and remote areas. Telstra’s mobile network covers 99.7% of the Australian population over an area of 3 million square kilometers. The company said it has invested $11.8 billion into its mobile network in Australia over the past seven years. As satellite technology advances, Telstra plans to look into voice, data and IoT services.

T-Mobile, AT&T and Verizon are all working on satellite-based text messaging services. Many D2D providers such as Starlink have promised text messaging services initially with plans to add more bandwidth-heavy applications, including voice and video, at a later date. “The first Starlink satellite direct to cell phone constellation is now complete,” SpaceX’s Elon Musk wrote on social media in December 2024. That’s good news for T-Mobile, which plans to launch a D2D service with Starlink in the near future. Verizon and AT&T and working with satellite provider AST SpaceMobile to develop their own D2D services.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

What is Satellite-to-Mobile technology?

Satellite-to-Mobile is one of the most exciting areas in the whole telco space and creates a future where outdoor connectivity for basic services, starting with text messages and, eventually, voice and low-rates of data, may be possible from some of Australia’s most remote locations. You may also hear it referred to as Direct to Handset or DTH technology.

What makes this technology so interesting is that for many people, they won’t need to buy a specific compatible phone to send an SMS over Satellite-to-Mobile, as it will take advantage of technology already inside modern smartphones.

Satellite-to-Mobile will complement our existing land-based mobile network offering basic connectivity where people have never had it before.* This technology will continue to mature and will initially support sending and receiving text messages, and in the longer term, voice and low speed data to smartphones across Australia when outdoors with a clear line of site to the sky. Just as mobile networks didn’t replace fibre networks, it’s important to realise the considerable difference between the carrying capacity of satellite versus mobile technology.

Who will benefit most from Satellite-to-Mobile technology?

Satellite-to-Mobile is most relevant to people in regional and remote areas of the country that are outside their carrier’s mobile coverage footprint.

Currently, Satellite-to-Mobile technology allows users to send a message only.

This is currently really a “just-in-case” connectivity layer that allows a person to make contact for help or let someone know they are ok when they are outside their own carrier’s mobile coverage footprint.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

References:

https://www.telstra.com.au/internet/starlink

https://www.telstra.com.au/exchange/telstra-to-bring-spacex-s-starlink-satellite-to-mobile-technolog

https://www.lightreading.com/satellite/telstra-taps-starlink-for-d2d-satellite-messaging-service

https://www.lightreading.com/satellite/amazon-d2d-offerings-are-in-development-

Telstra partners with Starlink for home phone service and LEO satellite broadband services

AT&T deal with AST SpaceMobile to provide wireless service from space

AST SpaceMobile: “5G” Connectivity from Space to Everyday Smartphones

AST SpaceMobile achieves 4G LTE download speeds >10 Mbps during test in Hawaii

AST SpaceMobile completes 1st ever LEO satellite voice call using AT&T spectrum and unmodified Samsung and Apple smartphones

AST SpaceMobile Deploys Largest-Ever LEO Satellite Communications Array

One NZ launches commercial Satellite TXT service using Starlink LEO satellites

New Zealand telco One NZ has commercially launched its Satellite TXT service to eligible phone customers [1.] enabling them to communicate via Starlin/SpaceX’s network of Low Earth orbit (LEO) satellites at no extra cost as long as they have a clear line of sight to the sky. The initial TXT service will take longer to send and receive TXT messages. In many cases, TXT messages will take 3 minutes. However, at times it may take 10 minutes or longer, especially during the first few months. As the service matures and more satellites are launched, we expect delivery times to improve. The type of eligible phone you are using, where you are in New Zealand and whether a satellite is currently overhead will all have an impact on whether your TXT is sent or received and how long it takes.

Note 1. There are only four handsets that can currently use of Satellite TXT: Samsung’s Galaxy Z Flip6, Z Fold6, and S24 Ultra, plus the OPPO Find X8 Pro. One NZ said the handset line-up will expand during the course of next year (2025).

“We have lift-off! I’m incredibly proud that One NZ is the first telecommunications company globally to launch a nationwide Starlink Direct to Mobile service, and One NZ customers are among the first in the world to begin using this groundbreaking technology,” exclaimed Joe Goddard, experience and commercial director at One NZ. He said coverage is available across the whole of New Zealand including the 40% of the landmass that isn’t covered by terrestrial networks – plus approximately 20 km out to sea. “Right from the start we’ve said we would keep customers updated with our progress to launch in 2024 and as the technology develops. Today is a significant milestone in that journey,” he added.

April 2023’s partnership with Starlink coincided with the beginning of a new era for One NZ, which up until that point had operated under the Vodafone brand. At the time, One NZ tempered expectations by making it clear the service wouldn’t launch until late 2024.

SpaceX in October finally received permission to begin testing Starlink’s direct-to-cell capabilities with One NZ. Later that same month, One NZ reported that its network engineers in Christchurch were successfully sending and receiving text messages over the network. “We continue to test the capabilities of One NZ Satellite TXT, and this is an initial service that will get better. For example, text messages will take longer to send but will get quicker over time,” said Goddard. He also went to some lengths to point out that Satellite TXT “is not a replacement for existing emergency tools, and instead adds another communications option.”

One NZ offered a few tips to help their customers use the service:

- To TXT via satellite, you need a clear line of sight to the sky. Unlike other satellite services, you don’t need to hold your phone up towards the sky.

- Keeping your TXT short will help. You can also prepare your TXT and press send as soon as you see the One NZ SpaceX banner appear on-screen.

- To check if your TXT has been delivered, check the time stamp next to your TXT. On a Samsung or OPPO, tap on the message.

- Remember to charge your phone or take a battery pack if you are out adventuring.

One NZ vs T-Mobile Direct to Cell Service:

New Zealand’s terrain – as varied and at times challenging as it is – can be covered by far fewer LEO satellites than the U.S. where T-Mobile has announced Direct to Cell service using Starlink LEO satellites. T-Mobile was granted FCC approval for the service in November, and is now signing up customers to test the US Starlink beta program “early next year.”

References:

https://one.nz/why-choose-us/spacex/

https://www.telecoms.com/satellite/one-nz-claims-direct-to-cell-bragging-rights-over-t-mobile-us

Space X “direct-to-cell” service to start in the U.S. this fall, but with what wireless carrier?

Space X “direct-to-cell” service to start in the U.S. this fall, but with what wireless carrier?

Starlink Direct to Cell service (via Entel) is coming to Chile and Peru be end of 2024

Starlink’s Direct to Cell service for existing LTE phones “wherever you can see the sky”

Satellite 2024 conference: Are Satellite and Cellular Worlds Converging or Colliding?

Reliance Jio vs Starlink: administrative process or auction for satellite broadband services in India?

Reliance Jio has argued that India’s telecom regulator incorrectly concluded that home satellite broadband spectrum should be allocated and not auctioned, according to a letter seen by Reuters. That intensifies Jio’s face-off with Elon Musk’s Starlink.

Starlink is expected to launch broadband satellite service in India soon after receiving a Global Mobile Personal Communication by Satellite (GMPCS) license. The Telecom Ministry has granted in-principle approval, and the Home Ministry is expected to finalize the vetting process. Starlink’s initial strategy was to provide satellite broadband directly to consumers, but the company may now only offer business services in India

India’s telecom regulator, TRAI, is holding a public consultation, but Reliance in a private Oct. 10 letter seen by Reuters asked for the process to be started afresh as the watchdog has “pre-emptively interpreted” that allocation is the way forward. “TRAI seems to have concluded, without any basis, that spectrum assignment should be administrative,” Reliance’s senior regulatory affairs official Kapoor Singh Guliani wrote in the letter to India’s telecoms minister Jyotiraditya Scindia.

References:

https://www.reuters.com/business/media-telecom/ambanis-reliance-lobbies-india-minister-satellite-spectrum-new-face-off-with-2024-10-13/

India’s TRAI releases Recommendations on use of Tera Hertz Spectrum for 6G

FCC: More competition for Starlink; freeing up spectrum for satellite broadband service

SpaceX launches first set of Starlink satellites with direct-to-cell capabilities

Communications Minister: India to be major telecom technology exporter in 3 years with its 4G/5G technology stack

India’s Trai: Coexistence essential for efficient use of mmWave band spectrum

OneWeb, Jio Space Tech and Starlink have applied for licenses to launch satellite-based broadband internet in India

Starlink to explore collaboration with Indian telcos for broadband internet services

FCC: More competition for Starlink; freeing up spectrum for satellite broadband service

More Competition for Starlink Needed:

FCC chairwoman Jessica Rosenworcel said Wednesday that she wants to see more competition for SpaceX‘s internet satellite constellation Starlink. Starlink (owned by SpaceX, which provides launch services) controls nearly two thirds of all active satellites and has launched about 7,000 satellites since 2018. Rosenworcel said at a conference Wednesday that Starlink has “almost two-thirds of the satellites that are in space right now and has a very high portion of (satellite)) internet traffic… Our economy doesn’t benefit from monopolies. So we’ve got to invite many more space actors in, many more companies that can develop constellations and innovations in space.”

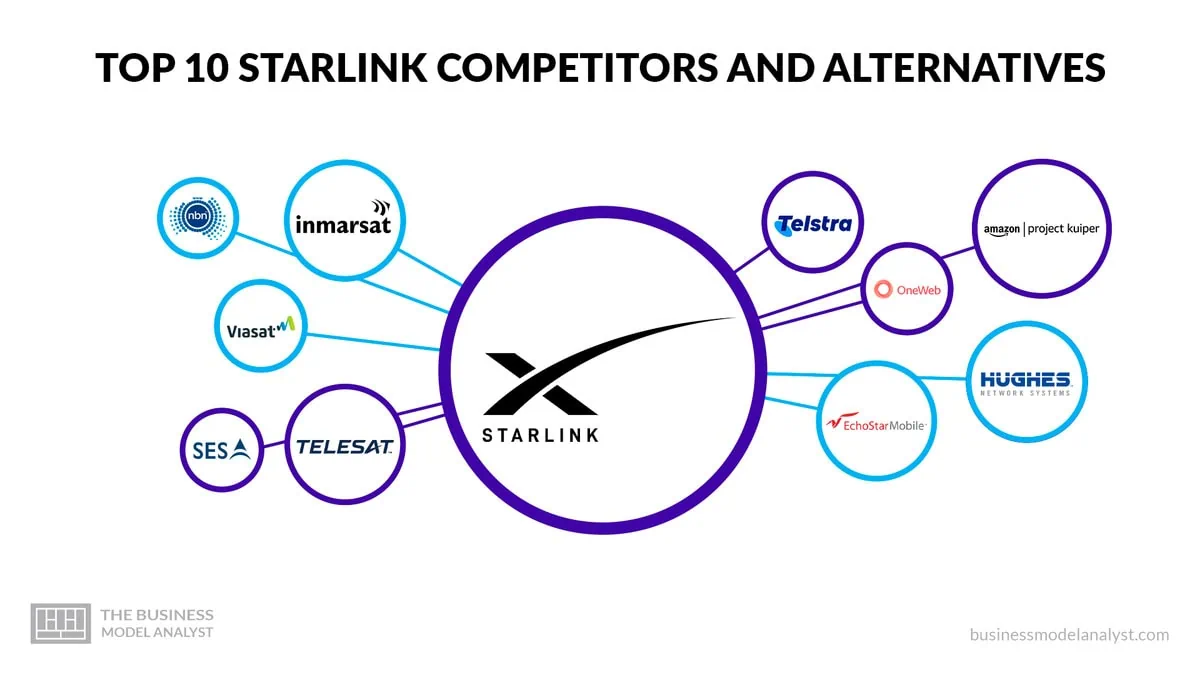

Starlink competitors include:

OneWeb is a solid alternative to Starlink’s satellite internet service by offering similar capabilities and coverage. The company plans to launch a constellation of approximately 650 satellites to provide seamless broadband connectivity to users worldwide, including remote and underserved areas. By operating in low-earth orbits (LEO), OneWeb’s satellites can offer low latency and high-speed internet access, suitable for a wide range of commercial, residential, and governmental applications. OneWeb’s satellites will be deployed in polar orbit, allowing them to cover even the Earth’s most remote regions. This global coverage makes OneWeb an attractive option for users who require internet connectivity in areas where traditional terrestrial infrastructure is limited or unavailable.

Viasat has a fleet of satellites in geostationary orbit, allowing it to provide internet services to customers in remote and rural areas. This coverage is essential for customers living in areas with limited terrestrial internet options. In addition to its satellite coverage, Viasat also offers competitive internet speeds. The company’s satellite technology allows fast and reliable internet connections, making it a viable alternative to traditional wired internet providers. This is especially beneficial for customers who require high-speed internet for activities such as streaming, online gaming, or remote work.

Telesat offers a wide range of satellite services tailored to different industries and applications. Telesat’s satellite fleet includes geostationary satellites, low-earth orbit (LEO) satellites, and high-throughput satellites (HTS), allowing it to deliver high-speed internet connectivity, broadcast services, and backhaul solutions to customers in remote and underserved areas. Telesat has extensive coverage and capacity in terms of satellite internet services. They have a strong presence in North America, South America, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa, making their services accessible to millions of users.

Telstra’s extensive network infrastructure and coverage make it a strong competitor to Starlink. The company operates a vast network of undersea cables, satellites, and terrestrial infrastructure, which enables it to provide reliable and high-speed connectivity across Australia and beyond. Telstra also has a solid customer base and brand recognition in the telecommunications industry, which gives it a competitive advantage. One of the critical business challenges that Telstra poses to Starlink is its established presence and dominance in the Australian market. Telstra has a significant market share and customer base in Australia, which gives it a strong foothold in the telecommunications industry. This makes it more difficult for Starlink to penetrate the market and attract customers away from Telstra. In addition, Telstra’s network coverage and infrastructure in remote and rural areas of Australia are competitive advantages.

Project Kuiper is backed by Amazon’s vast resources and infrastructure. Amazon’s deep pockets and logistics and cloud services expertise give Project Kuiper a decisive advantage in deploying and scaling its satellite network. By providing affordable and accessible broadband services, Project Kuiper intends to empower individuals, businesses, and communities with the opportunities and resources that come with internet access. With a constellation of low-earth orbit (LEO) satellites, Project Kuiper plans to deliver high-speed internet connectivity to areas with limited traditional terrestrial infrastructure.

Hughes Network System has a strong foothold in the market, particularly in rural areas with limited terrestrial broadband options. The company’s HughesNet service utilizes geostationary satellites to provide internet connectivity, offering up to 100 Mbps for downloads.

Inmarsat offers a range of satellite-based communication solutions that cater to its customers’ diverse needs. One key area where Inmarsat differentiates itself is its focus on mission-critical applications. The company’s satellite network is designed to provide uninterrupted and reliable connectivity, even in the most remote and challenging environments. Inmarsat’s portfolio includes services such as voice and data communications, machine-to-machine connectivity, and Internet of Things (IoT) solutions. The company’s satellite network covers most of the Earth’s surface, ensuring its customers can stay connected wherever they are.

Freeing Up Spectrum to Support Satellite Broadband Service:

At the FCC’s September 26th Open Commission Meeting, the Commission will consider a Report and Order that will provide 1300 megahertz of spectrum in the 17 GHz band for non-geostationary satellite orbit (NGSO) space stations in the fixed-satellite service (FSS) while also protecting incumbent operations. The Order provides a more cohesive global framework for FSS operators and maximizes the efficient use of the 17 GHz band spectrum. (IB Docket No. 22-273).

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

References:

https://www.fcc.gov/september-2024-open-commission-meeting

https://businessmodelanalyst.com/starlink-competitors/

SpaceX launches first set of Starlink satellites with direct-to-cell capabilities

Starlink Direct to Cell service (via Entel) is coming to Chile and Peru be end of 2024

SpaceX has majority of all satellites in orbit; Starlink achieves cash-flow breakeven

Starlink’s Direct to Cell service for existing LTE phones “wherever you can see the sky”

Amazon launches first Project Kuiper satellites in direct competition with SpaceX/Starlink

Momentum builds for wireless telco- satellite operator engagements

Over the past two years, the wireless telco-satellite market has seen significant industry-wide growth, driven by the integration of Non-Terrestrial Networks (NTN) in 5G New Radio as part of 3GPP Release 17. GSMA Intelligence reports that 91 network operators, representing about 5 billion global connections (60% of the total mobile market), have partnered with satellite operators. Although the regulatory landscape and policy will influence the commercial launch of these services in various regions, the primary objective is to achieve ubiquitous connectivity through a blend of terrestrial and non-terrestrial networks.

Recent developments include:

- AT&T and AST SpaceMobile have signed a definitive agreement extending until 2030 to create the first fully space-based broadband network for mobile phones. This summer, AST SpaceMobile plans to deliver its first commercial satellites to Cape Canaveral for launch into low Earth orbit. These initial five satellites will help enable commercial service that was previously demonstrated with several key milestones. These industry first moments during 2023 include the first voice call, text and video call via space between everyday smartphones. The two companies have been on this path together since 2018. AT&T will continue to be a critical collaborator in this innovative connectivity solution. Chris Sambar, Head of Network for AT&T, will soon be appointed to AST SpaceMobile’s board of directors. AT&T will continue to work directly with AST SpaceMobile on developing, testing, and troubleshooting this technology to help make continental U.S. satellite coverage possible.

- SpaceX owned Starlink has officially launched its commercial satellite-based internet service in Indonesia and received approvals to offer the service in Malaysia and the Philippines. Starlink is already available in Southeast Asia in Malaysia and the Philippines. Indonesia, the world’s largest archipelago with more than 17,000 islands, faces an urban-rural connectivity divide where millions of people living in rural areas have limited or no access to internet services. Starlink secured VSAT and ISP business permits earlier in May, first targeting underdeveloped regions in remote locations.Jakarta Globe reported the service costs IDR750,000 ($46.95) per month, twice the average spent in the country on internet service. Customers need a VSAT (very small aperture terminal) device or signal receiver station to use the solution.Internet penetration in Indonesia neared 80% at the end of 2023, data from Indonesian Internet Service Providers Association showed. With about 277 million people, Indonesia has the fourth largest population in the world. The nation is made up of 17,000 islands, which creates challenges in deploying mobile and fixed-line internet nationwide.Starlink also in received approvals to offer the service in Malaysia and the Philippines. The company aims to enable SMS messaging directly from a network of low Earth orbit satellites this year followed by voice and data starting in 2025. In early January, parent SpaceX launched the first of six satellites to deliver mobile coverage.

- Space X filed a petition with the FCC stating that it “looks forward to launching commercial direct-to-cellular service in the United States this fall.” That will presumably be only for text messages, because the company has stated that ONLY text will available in 2024 via Starlink. Voice and data won’t be operational until 2025. Importantly, SpaceX did not identify the telco who would provide Direct-to Cell satellite service this fall.

In August 2022, T-Mobile and SpaceX announced their plans to expand cellular service in the US using low-orbit satellites. The service aims to provide direct-to-cell services in hard-to-reach and underserved areas such as national parks, uninhabited areas such as deserts and mountain ranges, and even territorial waters. Traditional land-based cell towers cannot cover most of these regions.

- SpaceX said that “supplemental coverage from space (“SCS”) will enable ubiquitous mobile coverage for consumers and first responders and will set a strong example for other countries to follow.” Furthermore, SpaceX said the “FCC should reconsider a single number in the SCS Order—namely, the one-size-fits-all aggregate out-of-band power flux-density (“PFD”) limit of -120 dBW/m2 /MHz that it adopted in the new Section 25.202(k) for all supplemental coverage operations regardless of frequency band.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

References:

https://about.att.com/story/2024/ast-spacemobile-commercial-agreement.html

AT&T, AST SpaceMobile draw closer to sat-to-phone launch

Starlink sat-service launches in Indonesia

Space X “direct-to-cell” service to start in the U.S. this fall, but with what wireless carrier?

Japan telecoms are launching satellite-to-phone services

Japanese telecom carriers are rushing to launch communication services that directly connect smartphones to satellites. In recent years, global telecom carrier interest in non-terrestrial networks, such as space-based services, has grown. Such network services not only allow for expanded coverage to places that would otherwise be difficult to reach, but also are expected to be used in natural disasters. After the January 2023 Noto Peninsula Earthquake in Japan, SpaceX owned Starlink satellite internet service was used for emergency restoration of base stations and to provide internet at disaster shelters.

- Rakuten Mobile Inc. announced Friday that it will start offering a satellite-to-smartphone service that can also be used to make voice calls as early as 2026. The service is expected to provide a connection anywhere in the country, including in mountainous regions and areas offshore, where it is difficult to build base stations. It could prove useful in a natural disaster.

- KDDI Corp. also plans to launch a satellite-to-smartphone service for text messaging. Such satellite-based services do not require a dedicated receiver, and can be accessed with just a smartphone.

For the Rakuten Mobile service, the company will use satellites from AST SpaceMobile Inc., a U.S. startup that has been invested in by the Rakuten Group.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

AST SpaceMobile has launched two test satellites into low-earth orbit at an altitude of about 500 kilometers. Because these satellites orbit lower than geostationary satellites, they can provide communications with less delay. The company plans to have as many as 90 satellites operating in the future.

At a press conference on Friday, Rakuten Mobile Chairman Hiroshi Mikitani said, “Our customers will be able to enjoy mobile connectivity across Japan, even offshore or on an airplane.”

KDDI, which has gotten out ahead by providing access to Starlink, a satellite-based communication network from U.S. company SpaceX, will launch its text messaging service as early as this year.

Starlink currently requires a dedicated terminal, but last month SpaceX successfully launched six satellites that allow smartphones to connect to them directly.

NTT Docomo Inc. and SoftBank Corp. are looking to commercialize high-altitude platform stations, or HAPS. These stations are large unmanned aircraft that stay in the air at an altitude of about 20 kilometers, from where they send out radio signals.

NTT Docomo is currently testing direct links between HAPS and smartphones, and expects to launch a HAPS mobile service in fiscal 2025. However, a framework for space- and air-based services is still being defined.

The frequency bands to be used for the services are expected to be discussed at an international conference, and the Internal Affairs and Communications Ministry is considering technical requirements.

References:

SpaceX launches first set of Starlink satellites with direct-to-cell capabilities

Starlink Direct to Cell service (via Entel) is coming to Chile and Peru be end of 2024

KDDI Partners With SpaceX to Bring Satellite-to-Cellular Service to Japan

Telstra partners with Starlink for home phone service and LEO satellite broadband services

SpaceX has majority of all satellites in orbit; Starlink achieves cash-flow breakeven

Starlink’s Direct to Cell service for existing LTE phones “wherever you can see the sky”

AST SpaceMobile: “5G” Connectivity from Space to Everyday Smartphones

SpaceX launches first set of Starlink satellites with direct-to-cell capabilities

T-Mobile US today said that SpaceX launched a Falcon 9 rocket on Tuesday with the first set of Starlink satellites that can beam phone signals from space directly to smartphones. The U.S wireless carrier will use Elon Musk-owned SpaceX’s Starlink satellites to provide mobile users with network access in parts of the United States, the companies had announced in August 2022. The direct-to-cell service at first will begin with text messaging followed by voice and data capabilities in the coming years, T-Mobile said. Satellite service will not be immediately available to T-Mobile customers; the company said that field testing would begin “soon.”

/cloudfront-us-east-2.images.arcpublishing.com/reuters/73PVHSXKT5LIHDTFDWHUSDQTL4.jpg)

SpaceX plans to “rapidly” scale up the project, according to Sara Spangelo, senior director of satellite engineering at SpaceX. “The launch of these first direct-to-cell satellites is an exciting milestone for SpaceX to demonstrate our technology,” she said.

Mike Katz, president of marketing, strategy and products at T-Mobile, said the service was designed to help ensure users remained connected “even in the most remote locations”. He said he hoped dead zones would become “a thing of the past”.

Other wireless providers across the world, including Japan’s KDDI, Australia’s Optus, New Zealand’s One NZ, Canada’s Rogers will collaborate with SpaceX to launch direct-to-cell technology.

References:

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2024/jan/03/spacex-elon-musk-phone-starlink-satellites

Starlink Direct to Cell service (via Entel) is coming to Chile and Peru be end of 2024

Starlink’s Direct to Cell service for existing LTE phones “wherever you can see the sky”

Starlink Direct to Cell service (via Entel) is coming to Chile and Peru be end of 2024

Chilean network operator Entel and SpaceX, the company that owns satellite internet provider Starlink, made a commercial agreement to provide satellite-to-mobile services. The agreement will improve broadband coverage for Entel’s LTE customers. It will allow millions of cell phones in Chile and Peru to access satellite coverage starting at the end of 2024.

The first Starlink satellites with Direct to Cell capacity will be launched, providing basic satellite connectivity by the end of 2024. Starlink is a pioneer in providing fixed broadband services through low-orbit satellite networks, which helped it to gain an advantage in the development of direct-to-cell technology.

Starlink satellites with Direct to Cell capabilities enable access to texting, calling, and browsing anywhere on land, lakes, or coastal waters. Direct to Cell will also connect IoT devices which have LTE cellular access.

“One of the great advantages of this proposal is that it will work using the same 4G VoLTE phones that exist in the market today. It does not require any special equipment or special software,” Entel network manager Luis Uribe told BNamericas. “This is an important advantage over traditional satellite solutions. It is a technology that is still evolving, it is being developed. We are going to explore [use cases] as [the technology] advances,” he added.

Although Entel’s mobile networks cover 98% of the populations of Chile and Peru, the Starlink deal will allow it to provide services in maritime territory or in areas that suffered natural disasters.

“It is a technology that has enormous potential as a result of its ability to cover areas that traditional networks cannot achieve,” Uribe said.

A so-called line of sight between device and satellite is required for direct-to-cell to work, meaning the technology might not work indoors or in dense forests. If available, terrestrial coverage will be prioritized.

While other companies are developing similar solutions, they are not as advanced as Starlink. “We see other solutions that also look interesting. To the extent that these do not involve special software or devices, they could be an option,” said Uribe.

Entel is also focused on 5G deployment, achieving a first-stage goal of connecting 270 localities from Arica in the north to Puerto Williams in the south in August.

The company is investing US$350mn in the entire deployment program. In October, Entel enabled NB-IoT at over 6,500 sites to boost connectivity for Internet of Things devices.

“From the point of view of the company’s internal processes, we are incorporating artificial intelligence and generative artificial intelligence tools,” said Uribe. The technologies are being used for automation processes and network optimization, among others.

References:

https://www.bnamericas.com/en/features/spotlight-the-entel-starlink-mobile-coverage-agreement

Starlink’s Direct to Cell service for existing LTE phones “wherever you can see the sky”

SpaceX has majority of all satellites in orbit; Starlink achieves cash-flow breakeven

SpaceX has majority of all satellites in orbit; Starlink achieves cash-flow breakeven

SpaceX accounts for roughly one-half of all orbital space launches around the world, and it’s growing its launch frequency. It also has a majority of all the satellites in orbit around the planet. This Thursday, majority owner & CEO Elon Musk tweeted, “Excited to announce that SpaceX Starlink has achieved breakeven cash flow! Starlink (a SpaceX subsidiary) is also now a majority of all active satellites and will have launched a majority of all satellites cumulatively from Earth by next year.”

There are some 5,000 Starlink satellites in orbit. Starlink satellites are small, lower-cost satellites built by SpaceX that deliver high-speed, space-based internet service to customers on Earth. Starlink can cost about $120 a month and there is some hardware to buy as well.

Starlink ended 2022 with roughly 1 million subscribers. The subscriber count now isn’t known, but it could be approaching 2 million users based on prior growth rates. SpaceX didn’t return a request for comment.

In 2021, Musk said SpaceX would spin off and take Starlink public once its cash flow was reasonably predictable.

A SpaceX rocket carriers Starlink satellites into orbit. PHOTO CREDIT: SPACEX

Starlink has been in the spotlight since last year as it helps provide Ukraine with satellite communications key to its war efforts against Russia.

Last month, Musk said Starlink will support communication links in Gaza with “internationally recognized aid organizations” after a telephone and internet blackout isolated people in the Gaza Strip from the world and from each other.

Musk has sought to establish the Starlink business unit as a crucial source of revenue to fund SpaceX’s more capital-intensive projects such as its next-generation Starship, a giant reusable rocket the company intends to fly to the moon for NASA within the next decade.

Starlink posted a more than six-fold surge in revenue last year to $1.4 billion, but fell short of targets set by Musk, the Wall Street Journal reported in September, citing documents.

SpaceX is valued at about $150 billion and is one of the most valuable private companies in the world.

References:

https://www.barrons.com/articles/elon-musk-spacex-starlink-86fe99ec?